Software is bloated! It’s a sentiment many of us share, and one that feels increasingly urgent.

I was inspired on this topic after reading Why Bloat Is Still Software’s Biggest Vulnerability by Bert Hubert. This, in turn, brought me back to another excellent piece, Is The Web Getting Slower? by DebugBear, which paints a concerning picture.

But the roots of this concern go deeper. Back in 1995, the Turing Award laureate Niklaus Wirth penned a seminal article: A Plea for Lean Software.

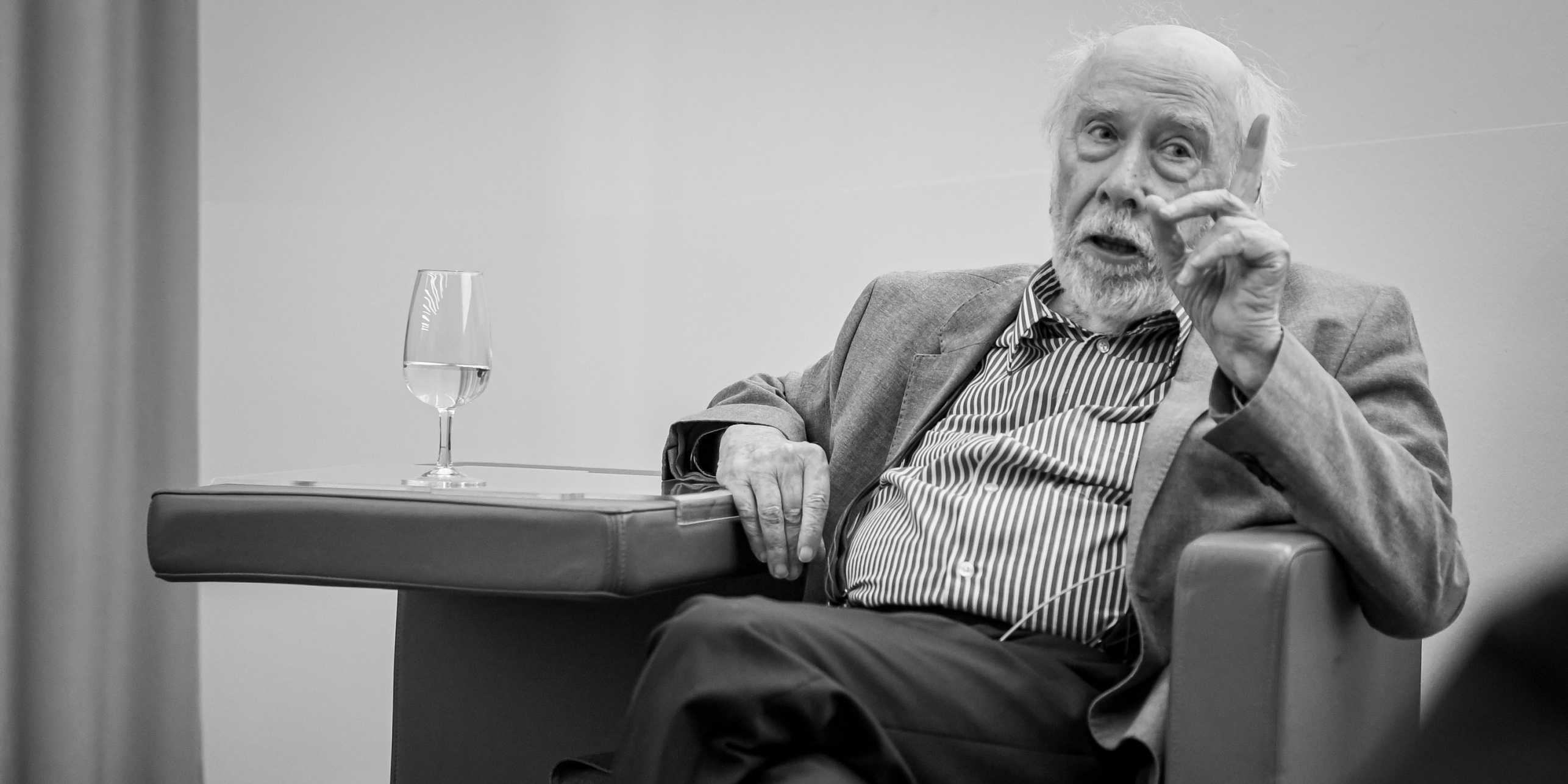

Photo: ETH Zurich / Andreas Bucher. The visionary Niklaus Wirth.

Photo: ETH Zurich / Andreas Bucher. The visionary Niklaus Wirth.

Wirth’s observations from nearly three decades ago are strikingly relevant today. He argued that software’s burgeoning size and complexity had far outpaced genuine advancements in functionality. Let’s revisit some of his key diagnoses.

Wirth’s Diagnosis: The Anatomy of ‘Fat Software’

1. Software Girth Surpassing Functionality (Bloat)

Wirth observed that software often requires vastly more memory and resources than older counterparts for similar core functionality. He echoed a sentiment often attributed to Parkinson: ‘Software expands to fill the available memory.’ And it seems hardware advances, while incredible, have often served to mask, rather than solve, this underlying bloat.

My take: Software’s girth has indeed surpassed its functionality in many areas, largely because hardware advances make this possible. It’s not surprising that hardware improvements sometimes hide software bloat problems. As Wirth suggested, ‘The way to streamline software lies in disciplined methodologies and a return to the essentials.’ I believe that embracing software best practices and first-principles-based thinking is a powerful combination here.

Why does this happen? According to Wirth:

‘Uncontrolled software growth has also been accepted because customers have trouble distinguishing between essential features and those that are just ‘nice to have.‘‘

2. Software Getting Slower Despite Faster Hardware

Another critical observation from Wirth was that ‘Software is getting slower more rapidly than hardware becomes faster.’ Bloated software, even on today’s incredibly fast hardware, can still feel sluggish. This paradox is a testament to the scale of inefficiency we’re dealing with.

3. Uncritical Adoption of Features & Monolithic Design

Wirth pointed to the tendency for vendors to add features indiscriminately, often based on user requests without considering the overall system integrity. This leads to complex, cumbersome systems where users pay a performance and resource penalty for a multitude of features they don’t use. The ‘all features, all the time’ approach contributes heavily to monolithic designs.

4. Self-Inflicted Complexity & Misinterpreting Complexity as Sophistication

‘People seem to misinterpret complexity as sophistication,’ Wirth cautioned. This is a dangerous trap. True sophistication often lies in simplicity and elegance, not in convoluted designs. Much of the complexity we grapple with is self-inflicted, arising from design choices rather than inherent problem difficulty.

5. Issues with Programming Languages

Wirth was critical of the prevailing programming languages of his time, particularly the widespread adoption of C, which he noted lacked secure type checking. He also felt C++‘s C compatibility hindered its ability to provide true type safety, stating, ‘Abstraction can work only with languages that postulate strict, static typing.’

6. Time Pressure Leading to Bulky, Poorly Designed Software

‘Time pressure is probably the foremost reason behind the emergence of bulky software,’ Wirth claimed. This resonates deeply. The pressure to ship quickly often discourages careful planning, iterative simplification, and thoughtful design, leading to accretions of code rather than refined solutions.

7. Lack of Iterative Improvement and Simplification

Wirth lamented the rarity of iterative improvement: ‘Truly good solutions emerge after iterative improvements… Evolutions of this kind, however, are extremely rare.’ This continuous refinement is crucial for shedding unnecessary weight and complexity over time.

A Modern Path Towards Leaner Software: Enter Zig

So, how do we fight back against this tide of bloat in modern software development? Wirth himself championed solutions through projects like Oberon, emphasizing modules, extensibility, and concentrating on essentials. While disciplined methodologies are paramount, the tools we wield—our programming languages—also play a significant role.

This brings me to a language I’ve been researching that seems to embody many of Wirth’s ideals: Zig.

Zig is a general-purpose systems programming language designed with a pragmatic focus on performance, robustness, simplicity, and, crucially, explicitness. It doesn’t magically solve all software engineering problems, but its design philosophy and technical features provide developers with excellent tools and encourage a mindset conducive to building software that is leaner, faster, simpler, and more robust.

Let’s explore how Zig’s approach aligns with Wirth’s plea:

Confronting Bloat with Explicitness and Control

Zig challenges the ‘software expands to fill available memory’ maxim head-on:

- Manual Memory Management: Zig gives developers explicit control over memory allocation and deallocation. There’s no hidden garbage collector making opaque decisions. Instead, you use explicit allocators. This forces a constant awareness of memory usage, a cornerstone of lean development.

- ‘No Hidden Allocations’: Functions requiring dynamic memory typically take an allocator instance as an argument. This transparency means no unexpected memory consumption from libraries or language constructs, directly addressing Wirth’s concern about software’s ‘ravenous appetite.’

comptime: Power Without Runtime Fat

Wirth advocated for basic systems with essential facilities that could be extended. Zig’s comptime feature is a modern answer to this:

- Compile-Time Metaprogramming:

comptimeallows Zig code to be executed during compilation. This powerful, unified mechanism can generate specialized code, enable conditional compilation, and build generic systems without runtime overhead or bloating the core language. - Extensible Systems from a Small Core: You can define features that are included or excluded at compile time, ensuring the final binary only contains what’s necessary. This is akin to Wirth’s Oberon, where modules could be loaded on demand, but Zig achieves much of this customization at compile time.

Simplicity as a Guiding Principle

Wirth warned against misinterpreting complexity as sophistication. Zig’s design embraces simplicity:

- Minimalist Language: Zig deliberately avoids features known for introducing undue complexity, like operator overloading or intricate class hierarchies. Its syntax is designed to be small and easy to learn.

- ‘No Hidden Control Flow’: Code in Zig does what it appears to do. There are no hidden function calls or unexpected side effects from destructors. This transparency is vital for understanding and maintaining lean systems.

Performance and Small Binaries

Aligning with Wirth’s desire for efficiency, Zig aims for C-like performance (or better) and can produce very small executables by default, as it doesn’t bundle a large runtime or GC.

Addressing Wirth’s ‘Causes for Fat Software’

Zig’s features offer potential mitigations for many issues Wirth raised:

- Developer Complacency vs. Hardware: Zig’s low-level control demands developer discipline, countering the tendency for hardware to hide sloppy design.

- Monolithic Design: Zig’s module system and its build system (which uses

build.zigfiles written in Zig) facilitate modular architectures.comptimefurther allows building extensible systems from a small core. - Time Pressure: Zig’s fast compilation times, integrated build system, and explicit error handling (which can reduce debugging time for certain error classes) can help manage development pressures without unduly sacrificing quality.

- Strong Typing: Echoing Wirth’s first lesson from Project Oberon (‘The exclusive use of a strongly typed language…’), Zig is statically typed, catching many errors at compile time.

The Wirthian Trade-off: Discipline Required

While Zig provides powerful tools, it’s not a panacea. The control it offers, especially manual memory management, comes with responsibility. Writing lean, robust software in Zig, as in any language aspiring to these ideals, requires significant developer discipline, careful thought, and a commitment to iterative refinement.

Zig can be seen as a ‘high-discipline’ language. It doesn’t make lean software easy by abstracting away all complexities of the machine. Instead, it makes lean software possible by demanding developer awareness and precision. This echoes Wirth’s emphasis: ‘The way to streamline software lies in disciplined methodologies and a return to the essentials.’ Zig provides a modern toolkit for those willing to embrace that discipline.

Conclusion: Carrying the Torch for Lean Software

Niklaus Wirth’s plea from 1995 is more relevant than ever. The fight against software bloat is ongoing, and it requires a conscious effort from all of us in the software field. While no single language is a silver bullet, languages like Zig, with their emphasis on simplicity, control, and explicitness, offer a promising path forward.

They remind us that performance, efficiency, and understandability are not just ‘nice-to-haves’ but are fundamental to crafting quality software. By embracing the principles Wirth championed and leveraging tools that support them, we can strive to build software that is not just functional, but truly lean and elegant.

What are your thoughts on software bloat and the tools or techniques you use to combat it?